Promises

- Promises

A “promise” is a surrogate entity that acts as a stand-in for a result that does not yet exist.

本文分为五个章节。第一章节简单讲了下 Promise 的由来。第二章节讲了下 Promise 的一些基础知识。依次讲了:状态机及其特征,executor的两个任务,如何初始化一个 fufilled 状态的Promise,同步/异步执行的二元性。第三章节讲了下 Promise 实例对象上的一些方法以及resolve和reject。第四章节讲了下两类组合多个 Promise 的方法:chaining 和 composition。 第五章节讲了下 Promise 的扩展应用。

The Promises/A+ Specification

Early forms of promises appeared in jQuery and Dojo’s Deferred API. In 2010, growing popularity led to the Promises/A specification inside the ComonJS project. Third-party JavaScript promise libararies continued to gain adoption, yet each implementation was slightly different. To address the rifts in the promise space, in 2012 the Promises/A+ organization forked the CommonJS “Promises/A” proposal and created the eponymous Promises/A+ Promise Specification (https://promisesaplus.com/).

This specification would eventually govern how promises were implemented in the ECMAScript 6 specification.

Multiple browser APIs such as fetch() and the battery API use it exclusively.

Promise Basics

The Promise reference type can be instantiated with the new operator. Doing so requires passing an executor function parameter.

let executor = () => {}

let p = new Promise(executor);

setTimeout(console.log, 0, p); // Promise <pending>

An executor is a function, which will contain some codes. We can put the asynchronous behaviors here. We will explain it further latter.

In this section, we do not use the then method, we only care about the internal state of promise.

And in this section, we use setTimeout(console.log, 0, p) to print information.

The Promise State Machine

先不考虑executor的具体使用, 只考虑Promise的状态变化.

-

State machine:

A promise is a stateful object that can exist in one of three state:- Pending

- Fulfilled (sometimes also refered to as resolved)

- Rejected

A pending state is the initial state a promise begins in. From a pending state, a promise can become settled by transitioning to a fulfilled state to indicate success, or a rejected state to indicate failure.

- Features

- This transition to a settled state is irreversible.

- It is not guaranteed that a promise will ever leave the pending state.

- The state of a promise is private and cannot be directly inspected in JavaScript. The reason for this is primarily to prevent synchronous programmatic handling of a promise object based on its state when it is read.

- Furthermore, the state of a promise cannot be mutated by external JavaScript. So that you cannot control the state manually.

- 总结: 不保证执行, 一旦执行不可逆转, 不能读取状态, 不能修改状态

- Why we cannot directly inspect and mutate the state of a promise?

The promise intentionally encapsulates a block of asynchronous behavior, and external code performing synchronous definition of its state would be antithetical to its purpose.

Controlling Promise State with the Executor

开始考虑 executor。

-

A promise abstractly represent a block of asynchronous execution. The state of the promise is indicative of whether or not the promise has yet to complete execution.

-

Because the state of a promise is private, it can only be manipulated internally. This internal manipulation is performed inside the promise’s executor function.

- The executor function has two primary duties

- initializing the asynchronous behavior of the promise

- controlling any eventual state transition.

- For the first duty. We wrap the asynchronous behaviors in it. The executor function will execute synchronously, as it acts as the initializer for the promise. However, when encountering asynchronous function call, they will not execute immediately#, but just act as skip it.

resolveandrejectare asynchronous too, which allow us to set the handler latter withthenorcatch.const p = new Promise((resolve) => { console.log(1); resolve(); console.log(2); }); console.log(3); // 1 // 2 // 3 - For the second duty. Control of the state transition is accomplished by invoking one of its two function parameters, typically named

resolveandreject. Invokingresolvewill change the state to fulfilled; invokingrejectwill change the state to rejected. Invokingrejected()will also throw an error (this error behavior is covered more later).let p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => resolve(1)); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p1); // Promise <resolved> let p2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => reject(2)); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2); // Promise <rejected> // Uncaught error (in promise) let p3 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => throw Error("error")); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2); // Promise <rejected> // Uncaught error (in promise) - Furthermore, every promise that transitions to a fulfilled state has a private internal value. Similarly, every promise that transitions to a rejected state has a private internal reason. They are settled by parameter of

rejectorresolve.

Promise Casting with Promise.resolve()

- It is possible to instantiate a promise in the “resolved” state by invoking the

Promise.resolve()static method without executor function. The following two promise instantiations are effectively equivalent:let p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => resolve()) let p2 = Promise.resolve(); - This effectively allows you to “cast” any value into a promise, even the error object:

setTimeout(console.log, 0, Promise.resolve()); // Promise <resolved>: undefined setTimeout(console.log, 0, Promise.resolve(3)); // Promise <resolved>: 3 setTimeout(console.log, 0, Promise.resolve(new Error('foo'))); // Promise <resolved>: Error: foo // Additional arguments are ignored setTimeout(console.log, 0, Promise.resolve(4, 5, 6)); // Promise <resolved>: 4 - Perhaps the most important aspect of this static method is its ability to act as a passthrough when the argument is already a promise. As a result,

Promise.resolve()is an idempotent method. This idempotence will respect the state of the promise passsed to it:let p = new Promise(() => {}); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p);// Promise <pending> setTimeout(console.log, 0, Promise.resolve(p)); // Promise <pending> setTimeout(console.log, 0, p === Promise.resolve(p)); // true - For a thenable object, which implements the

thenmethod,Promise.resolvewill unwrap the object and try to get a value, and then rewrap the value into a new Promise object. Thethenmethod accept two arguments:onFulfilled(resolve) andonRejected(reject), both they are methods. #const thenable = { then: function (resolve, reject) { resolve("Resolving"); // throw new TypeError("Throwing"); }, }; const p = Promise.resolve(thenable); console.log(p instanceof Promise); // true setTimeout(console.log, 0, p); // Promise{<fulfilled>: "Resolving"}

Promise Rejection with Promise.reject()

- Similar in concept to

Promise.resolve(),Promise.reject()instantiates a rejected promise and throws an asynchronous error (which will not be caught by try/catch and can only be caught by a rejection handler). The following two promise instantiations are effectively equivalent:let p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => reject()); let p2 = Promise.reject(); - Importantly,

Promise.reject()does not mirror the behavior ofPromise.resolve()with respect to idempotence. If passed a promise object, it will happily use that promise as the ‘reason’ field of the rejected promise:setTimeout(console.log, 0, Promise.reject(Promise.resolve())); // Promise <rejected>: Promise <resolved>

Synchronous/Asynchronous Execution Duality

try {

throw new Error("foo");

} catch (e) {

console.log(e); // Error: foo

}

try {

Promise.reject(new Error("bar"));

} catch (e) {

console.log(e);

}

// Uncaught (in promise) Error: bar

the reason the second promise is not caught is that the code is not attempting to catch the error in the appropriate “asynchronous mode.” Such behavior underscores how promises actually behave: They are synchronous objects—used inside a synchronous mode of execution—acting as a bridge to an asynchronous mode of execution.

Promise Instance Methods

Implementing the Thenable Interface

// since js do not have `interface` in other languages, it should use class to simulate interfce.

class MyThenable {

then() {}

}

Any object that exposes a then() method is considered to implement the Thenable interface.

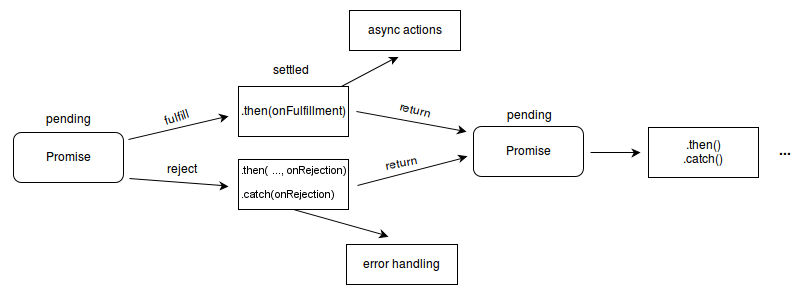

Promise.prototype.then()

-

Remind that in an executor, the code will execute in order just as they are not wrapped in the Promise. However, when it encounter the handler

resolveorreject, they will be skiped and invoked again latter, which is convenient for us so set handlers latter. We set them bythen. - The

then()method accepts up to two arguments: an optionalonResolvedhandler function, and an optionalonRejectedhandler function. Each will execute only when the promise upon which they are defined reaches its respective “fulfilled” or “rejected” state. Both handler arguments are completely optional. Any non-function type provided as an argument tothen()will be silently ignored.new Promise(() => {}).then(undefined, (reason) => { throw reason; }) -

Immutable. The

Promise.prototype.then()method returns a new promise instance. The instance is return by theonResolvedoronRejecthandler. - For the

onResolvedhandler, the new promise instance is derived from the return value of theonResolvedhandler. The return value of the handler is wrapped inPromise.resolve()to generate a new promise.- If no handler function is provided, the method acts as a passthrough for the initial promise’s resolved value. the

onResolvedfunction just act like this:(value) => value - If there is no explicit return statement, the default return value is

undefinedand wrapped in aPromise.resolve(). - Explicit return values are wrapped in

Promise.resolve(). Note thatPromise.resolve()preserves the returned promise. - Throwing an exception will return a rejected promise.

- Importantly, returning an error will not trigger the same rejection behavior, and will instead wrap the error object in a resolved promise:

const p = Promise.resolve(1) // Promise <resolved>: 1 const p2 = p.then(2); // Promise <resolved>: 1 // 1 const p3 = p.then(); // Promise <resolved>: 1 // 2 const p4 = p.then(a => {}); // Promise <resolved>: undefined const p5 = p.then(() => undefined); // Promise <resolved>: undefined // 3 const p6 = p.then(a => a + 1); // Promise <resolved>: 2 const p7 = p.then(() => 2); // Promise <resolved>: 2 const p8 = p.then(() => Promise.resolve(2)); // Promise <resolved>: 2 const p9 = p.then(() => Promise.reject("err")); // Promise <rejected>: undefined // Uncaught (in promise) undefined // 4 const p10 = p.then(() => {throw "err"}); // Promise <rejected>: err // 5 const p11 = p.then(() => Error('qux')); // Promise <resolved>: Error: qux - If no handler function is provided, the method acts as a passthrough for the initial promise’s resolved value. the

- The

onRejectedhandler behaves in the same way: values returned from theonRejectedhandler are wrapped inPromise.resolve().const p = Promise.reject(1); // Promise <rejected>: 1 const p2 = p.then(undefined, () => 2); // Promise <resolved>: 2 const p3 = p.then(undefined, () => Promise.resolve(2)) // Promise <resolved>: 2

Promise.prototype.catch()

promise.catch(onRejected) is equivalent to promise.then(null, onRejected) in result.

Promise.prototype.finally()

-

The

Promise.protoype.finally()method can be used to attach anonFinallyhandler, which executes when the promise reaches either a resolved or a rejected state. -

This is useful for avoiding code duplication between

onResolvedandonRejectedhandlers. Importantly, the handler does not have any way of determining if the promise was resolved or rejected, so this method is designed to be used for things like cleanup. -

It returns a new promise instance.

- Differ from

thenandcatch, becauseonFinallyis intended to be a state-agnostic method, in most cases it will behave as a passthrough for the parent promise, whatever what type of value returned in handler. (In this situation it just act asPromise.resolve(promise), except that it do not returns a new instance)const p = Promise.resolve(1); const p2 = p.finally(() => 2); const p3 = Promise.resolve(p); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p) // Promise <resolved> 1 setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2) // Promise <resolved> 1 // still 1 ! setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2) // Promise <resolved> 1 setTimeout(console.log, 0, p === p2) // false setTimeout(console.log, 0, p === p3) // true const p4 = p.finally(() => Promise.resolve(2)); // Promise <resovled> 1 const p5 = p.finally(() => Error("err")); // Promise <resolved> 1 - The only exceptions to this are when it returns a pending promise, or an error is thrown (via an explicit throw or returning a rejected promise). In these cases, the corresponding promise is returned (pending or rejected)

const p6 = p.finally(() => new Promise(() => {})); // Promise <resovled> 1 (dangerous operation, for the reason listed in 6) const p7 = p.finally(() => Promise.reject("err")); // Promise <resovled> 1 const p8 = p.finally(() => { throw "err"; }); // Uncaught (in promise) err setTimeout(console.log, 0, p6) // Promise <pending> setTimeout(console.log, 0, p7) // Promise <rejected> err setTimeout(console.log, 0, p8) // Promise <rejected> err - Returning a pending promise is an unusual case, as once the promise resolves, the new promise will still behave as a passthrough for the initial promise

let p1 = Promise.resolve("foo"); // The resolved value is ignored const p2 = p1.finally( () => new Promise((resolve, reject) => setTimeout(() => resolve("bar"), 100)) ); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2); // Promise <pending> setTimeout(console.log, 0, p1 === p2); // false setTimeout(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2), 200); // After 200ms: // Promise <resolved>: foo setTimeout(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, p1 === p2), 200); // false

Non-Reentrant Promise Methods

- When a promise reaches a settled state, execution of handlers associated with that state are merely scheduled (push on to message queue) rather than immediately executed. Synchronous code following the attachment of the handler is guaranteed to execute before the handler is invoked. This property, called non-reentrancy, is guaranteed by the JavaScript runtime (event loop).

// create a resolved let p = Promise.resolve(); // Attach a handler to the resolved state p.then(() => console.log("onResolved handler")) // Synchronously log to indicate that then() has returned console.log('then() returns') // Actual output: // then() returns // onResolved handler - If handlers (all the onResolved, onReject, onFinally) are already attached to a promise that later synchronously changes state, the handler execution is non-reentrant upon that state change. The following example demonstrates how, even with an

onResolvedhandler already attached, synchronously invokingresolve()will still exhibit non-reentrant behavior (只要将 handler attach 到了promise 上, 它的执行就变成了 non-reentrant 的, 即使它又被某种方式保存到promise外并执行):let synchronousResolve; // Create a promise and capture the resolve function in a local variable let p = new Promise((resolve) => { synchronousResolve = function () { console.log("1: invoking resolve()"); resolve(); console.log("2: resolve() returns"); }; }); p.then(() => console.log("4: then() handler executes")); synchronousResolve(); console.log("3: synchronousResolve() returns"); // Actual output: // 1: invoking resolve() // 2: resolve() returns // 3: synchronousResolve() returns // 4: then() handler executes

Sibling Handler Order of Execution

If multiple handlers are attached to a promise, when the promise transitions to a settled state, the associated handlers will execute in the order in which they were attached. This is true for then(), catch(), and finally():

let p1 = Promise.resolve();

let p2 = Promise.reject();

p1.then(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 1));

p1.then(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 2));

// 1

// 2

p2.then(null, () => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 3));

p2.then(null, () => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 4));

// 3

// 4

p2.catch(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 5));

p2.catch(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 6));

// 5

// 6

p1.finally(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 7));

p1.finally(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 8));

// 7

// 8

Resolved Value and Rejected Reason Passing

let p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => resolve('value'));

p1.then((value) => console.log(value)); // value

let p2 = Promise.reject('reason');

p2.catch((value) => console.log(value)); // reason

Rejecting Promises and Rejection Error Handling

- Throwing an error inside a promise executor or handler will cause it to reject; the corresponding error object will be the rejection reason.

let p1 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => reject(Error('foo'))); let p2 = new Promise((resolve, reject) => { throw Error('foo'); }); let p3 = Promise.resolve().then(() => { throw Error('foo'); }); let p4 = Promise.reject(Error('foo')); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p1); // Promise <rejected>: Error: foo setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2); // Promise <rejected>: Error: foo setTimeout(console.log, 0, p3); // Promise <rejected>: Error: foo setTimeout(console.log, 0, p4); // Promise <rejected>: Error: foo -

Promises can be rejected with any value including

undefined, but it is strongly recommended that you consistently use error object. The primary reason for this is that constructing an error object allows the browser to capture the stack trace inside the error object, which is immensely useful in debugging. - If you catch the error manually with try/catch while still inside the executor, the next state will be ‘resovled’ rather than ‘rejected’

Promise Chaining and Composition

There are two primary ways to combine multiple promises together:

- promise chaining, which involves strictly sequencing multiple promises.

- promise composition, which involves combining multiple promises into a single promise.

Promise Chaining

- Promises can be strictly sequenced, since

then(),catch()andfinally()returns a separate promise instance, which in turn can have another instance method called upon it.let p = new Promise((resolve, reject) => { console.log("first"); resolve(); }) p.then(() => console.log('second')); p.then(() => console.log('third')); p.then(() => console.log('fourth')); // first // second // third // fourth - Because each successive promise will await the resolution of its predecessor, such a strategy can be used to serialize asynchronous tasks. For example, this can be used to execute multiple promises in serries that resolve after a timeout:

function delayedResolve(str) { return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { console.log(str); setTimeout(resolve, 1000); }); } delayedResolve("p1 executor") .then(() => delayedResolve("p2 executor")) .then(() => delayedResolve("p3 executor")) .then(() => delayedResolve("p4 executor")); // p1 executor (after 1s) // p2 executor (after 2s) // p3 executor (after 3s) // p4 executor (after 4s) - Without the use of promises, the preceding code would look something like this:

delayedExecute("p1 callback", () => { delayedExecute("p2 callback", () => { delayedExecute("p3 callback", () => { delayedExecute("p4 callback"); }); }); });

Promise Graphs

Forming directed acyclic graphs of chained promises is possible.

Parallel Promise Composition with Promise.all() and Promise.race()

Two static methods that allow you to compose a new promise instance out of several promise instances. The behavior of this composed promise is based on how the promises inside it behave.

Promise.all()- The static method accepts an iterable and returns a new promise. Elements in the iterable are coerced into a promise using

Promise.resolve().let p1 = Promise.all([ Promise.resovle(), Promise.resolve() ]); // Elements in the iterable are coerced into a promise using Promise.resolve() let p2 = Promise.all([3, 4]); p2.then((values) => setTimeout(console.log, 0, values)); // [3, undefined, 4] - The composed promise will only resolve once every contained promise is resolved. If at least one contained promise remains pending, the composed promise also will remain pending. If one contained promise rejects, the composed promise will reject.

- If all promises successfully resolve, the resolved value of the composed promise will be an array of all of the resolved values of the contained promises, in iterator order.

- If one of the promises rejects, whichever is the first to reject will set the rejection reason for the composed promise. Importantly, the composed promise will silently handle the rejection of all contained promises.

let p = Promise.all([ new Promise((resolve, reject) => setTimeout(reject, 1000)), Promise.reject(3), ]); p.catch((reason) => setTimeout(console.log, 0, reason)); // 3 // No unhandled errors

- The static method accepts an iterable and returns a new promise. Elements in the iterable are coerced into a promise using

Promise.race()- The

Promise.race()static method creates a promise that will mirror whichever promise inside a collection of promises reaches a resolved or rejected state first. The static method accepts an iterable and returns a new promise.// Resolve occurs first, reject in timeout ignored let p1 = Promise.race([ Promise.resolve(3), new Promise((resolve, reject) => setTimeout(reject, 1000)), ]); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p1); // Promise <resolved>: 3 // Reject occurs first, resolve in timeout ignored let p2 = Promise.race([ Promise.reject(4), new Promise((resolve, reject) => setTimeout(resolve, 1000)), ]); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p2); // Promise <rejected>: 4 // Iterator order is the tiebreaker for settling order let p3 = Promise.race([ Promise.resolve(5), Promise.resolve(6), Promise.resolve(7), ]); setTimeout(console.log, 0, p3); // Promise <resolved>: 5

- The

Serial Promise Composition

A core feature of promises: their ability to asynchronously produce a value and provide it to handlers. Chaining promises together with the intention of each successive promise using the value of its predecessor is a fundamental feature of promises.

Promise Extensions

Two offerings available in some third-party promise implementations but lacking in the formal ECMAScript specification are promise canceling and progress tracking.

Promise Canceling?

In ES6, once the promise’s encapsulated function is underway, there is no way to prevent this process from completing.

Promise Cancellation Is Dead — Long Live Promise Cancellation!

class CancelToken {

constructor(cancelFn) {

this.promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

cancelFn(() => {

setTimeout(console.log, 0, "delay cancelled");

resolve();

});

});

}

}

const startButton = document.querySelector('#start');

const cancelButton = document.querySelector('#cancel');

function cancellableDelayedResolve(delay) {

setTimeout(console.log, 0, "set delay");

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const id = setTimeout(() => {

setTimeout(console.log, 0, "delayed resolve");

resolve();

}, delay);

const cancelToken = new CancelToken((cancelCallback) =>

cancelButton.addEventListener("click", cancelCallback)

);

cancelToken.promise.then(() => clearTimeout(id));

});

}

startButton.addEventListener("click", () => cancellableDelayedResolve(1000));

Promise Progress Notifications?

An in-progress promise might have several discrete “stages” that it will progress through before actually resolving. In some situations, it can be useful to allow a program to watch for a promise to reach these checkpoints. ECMAScript 6 promises do not support this concept, but it is still possible to emulate this behavior by extending a promise.

We can use the Observer Pattern:

class TrackablePromise extends Promise {

constructor(executor) {

const notifyHandlers = [];

super((resolve, reject) => {

return executor(resolve, reject, (status) => {

notifyHandlers.map((handler) => handler(status));

});

});

this.notifyHandlers = notifyHandlers;

}

notify(notifyHandler) {

this.notifyHandlers.push(notifyHandler);

return this;

}

}

let p = new TrackablePromise((resolve, reject, notify) => {

function countdown(x) {

if (x > 0) {

notify(`${20 * x}% remaining`); // pass the state tag

setTimeout(() => countdown(x - 1), 1000);

} else {

resolve();

}

}

countdown(5);

});

p.notify((x) => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 'progress:', x)); // pass onNotified callback, which arg used to handle the state tag

p.then(() => setTimeout(console.log, 0, 'completed'));

// (after 1s) 80% remaining

// (after 2s) 60% remaining

// (after 3s) 40% remaining

// (after 4s) 20% remaining

// (after 5s) completed

Reference:

- Professional JavaScript for Web Developers 4th Edition

- Promises/A+

- Promise Cancellation Is Dead — Long Live Promise Cancellation!

- Promise.resolve